Our lives are becoming more and more dependent on space technologies. We use satellites for meteorology, communications, navigation, and observation of disaster areas. According to the European Space Agency, ESA, around 40% of modern-day mobile applications rely on satellite and space technology. However, this infrastructure is at risk.

95% of all objects in low-Earth orbit, which is to say at altitudes between 200 and 2000 kilometers, are defective and no longer controllable. They are space debris—such as jettisoned rocket stages, solar panels (including those from satellites), tools, paint chips, and particles of solid fuel. This debris poses a risk to active satellites and to future space missions and their crews. Even the International Space Station has had to maneuver to avoid space debris on several occasions.

Constellations of mini-satellites

The situation is becoming more urgent due to the new satellites that continue to be placed in orbit. Whereas only 50 spacecraft were sent into orbit each year between 2009 and 2012, 800 are scheduled for the current year, and the trend is upward. In the future, most of the new arrivals in space will be nanosatellites, as part of network constellations. For example, the company OneWeb began to build a constellation of around 650 mini-satellites in 2019. Their aim is to enable internet access even in the most remote locations on Earth. Projects like this, as well as the emerging field of space tourism, necessitate the removal of space debris.

With over 34,000 human-made objects currently registered with diameters exceeding ten centimeters, we have reached a critical juncture. If humanity doesn’t do anything about it, an estimated 140,000 objects of junk will accumulate in orbit by 2065. This is because the collision of two objects creates a debris field with a multitude of parts. There is a risk of a dangerous chain reaction.

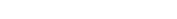

First debris removal mission by the ESA

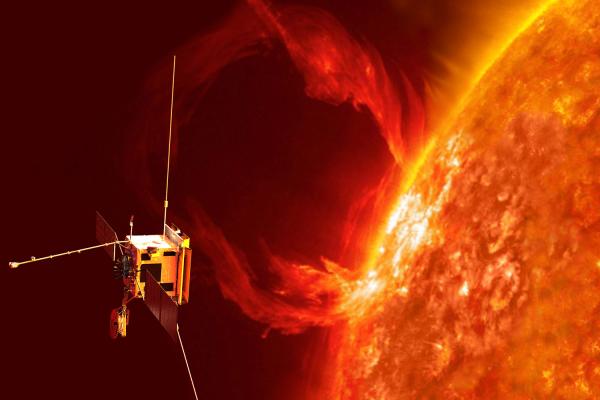

Now a Swiss “disposal satellite” is set to do the groundbreaking work of removing a debris object for the first time. Planned for 2025, the ClearSpace One mission, directed by the startup of the same name, will capture the discarded VESPA upper stage (VEga Secondary Payload Adapter) from a rocket launched in 2013 and guide it into the Earth’s atmosphere.

The prototype of this space cleaner will use a “chaser” consisting of four robotic arms to grab and move the disused upper stage at an altitude of 720 kilometers. Twelve maxon drives operate the tentacle-like arms of ClearSpace One. After that, the captured rocket stage will be positioned such that it can be decelerated out of orbit. This procedure will use jet engines on several sides. During a controlled reentry, both the VESPA and the ClearSpace One will burn up in the atmosphere—the biggest “incineration plant” ever.

The idea is that future disposal satellites will repeat this procedure as often as possible. They will also carry away heavier objects in low-Earth orbit to free up space for subsequent space operations.

The researchers at the EPFL Space Center in Switzerland have been working on space debris capture systems since 2010. The engineering knowledge they have gained over the years went into the development of ClearSpace One. In 2017, the project was spun off, resulting in the founding of ClearSpace SA, which began its operations in the maxon lab at the EPFL. As Luc Piguet, CEO and cofounder of ClearSpace SA, observed, “The maxon lab is a hub for technology transfer, making it ideal for startups.” The growing team at ClearSpace has been enhanced by specialist consultants from leading space agencies and companies with mission experience. The advisory board includes luminaries such as Jean-Jacques Dordain, former Director General of the ESA, and Swiss astronaut Claude Nicollier.

It is remarkable for a startup to be given responsibility for a EUR 100 million project. In 2019, ClearSpace prevailed single-handedly against Airbus, Thales Alenia Space (France), and Avio (Italy). Luc Piguet said, “Although we had great confidence in the application we submitted, we were surprised to be allowed to take the lead over a project consortium on our own.” He remained pragmatic, however: “We’ve taken economic considerations into account right from the beginning.” The costs incurred by each de-orbit should be as low as possible. This won over the ESA. Piquet added with a modest smile, “We’re taking on a big responsibility.”

ADRIOS programm

The ClearSpace One mission is part of the ESA’s space safety program ADRIOS (Active Debris Removal / In-Orbit Servicing). Its aim is to begin the removal of potentially dangerous space debris. It is hoped that this will pave the way for further missions that will contribute to the responsible development of space. Eight ESA member states, including Switzerland, are providing EUR 86 million for the project. The remaining EUR 14.2 million is coming from sponsors.

A 3D animation of all the pieces of debris orbiting the Earth can be viewed at stuffin.space

Author: Luca Meister