The air is heavy with the smell of lubricant oil. I am strolling through the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento, as a huge black monster appears before my eyes. Surrounded by a labyrinth of magnificent old locomotives, I admire the pioneers who completed the First Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, marveling at their achievements. However, there is something wrong with one of the machines.

Unobstructed tunnel vision

The locomotive answers to the name “Southern Pacific 4294” and was built in 1944. It has a reverse design, with the cab in front. The cramped control center of the venerable machine can be reached via a narrow ladder. In the cab, an older gentleman awaits me. He used to ride this iron horse across the western United States. His name is Bill, and he volunteers at the museum in his retirement. Children love listening to the old dinosaur when he proudly explains about his cab-forward locomotive. He still knows every single one of the numerous levers and valves by heart.

Since their initial opening, the tracks of the Sierra Nevada were a nightmare for train drivers. Tunnels alternated with snowy overhangs, trapping the steam and smoke from the machine so that it ended up in the eyes of the crew instead of rising skywards. Just around the time when petroleum engines became usable for railways, somebody built a steam locomotive with the cab in front of the boiler, for unobstructed tunnel vision.

Michael Funk (31)

is an academian and PhD candidate, essayist, writer, and musician. He studied philosophy, German, and history at TU Dresden. From 2007 to 2015, he worked as a researcher and lecturer at TU Dresden’s faculty of technological philosophy, before accepting an assistant professorship at the University of Vienna in 2016. Among other topics, his research covers the impact on society of social robotics, drones, and synthetic biology.

The reversal of cab and boiler – it was quite literally a revolution, but did it actually herald a new age? Bill laughs: “The real revolution came later, when they started using electric motors.” Even a brief tour of the museum leaves no doubt about what he means: The changed design of later locomotives, railway cars, and overhead lines is just too obvious.

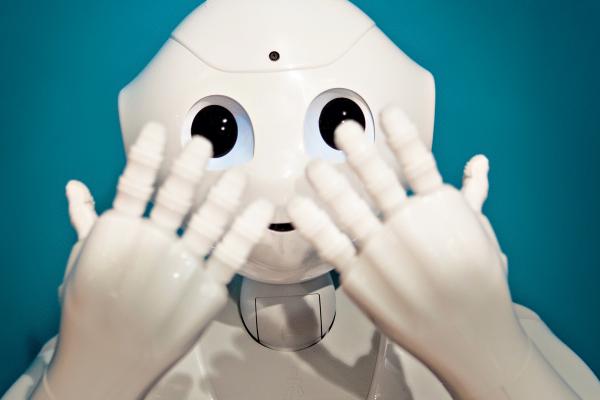

What past revolution will I be talking about when I reach dinosaur status? Maybe serving robots, or my first model railway from a 3D printer?

An elevator takes me to the second floor. I watch the elevator doors as they open and close, then repeat their mechatronical choreography shortly afterwards. We take this for granted. Along an endless skyline of locomotives and railway cars, I let my eyes pass over 150 years of technological history. A surveillance camera mimics my scan of the room, just as if it wanted to beat me to a selfie. What for? Who steals a multi-ton piece of equipment from a railway depot turned museum? Industrial espionage? In the digital new world maybe, but not here, in this nostalgic Eldorado of railway romantics!

Between rows of railway cars, Bill explains the history of workplace health and safety to a visitor. In the early days, for example with the postal service trains of the 1860s, the massive, rolling cars were hitched manually. If you weren’t quick enough, you might be one hand short. Today we have strict rules, artificial joints, and high-tech prostheses. Accidents drive progress. However, who’s going to regulate or insure packet delivery drones – before accidents happen?

So many things that we take for granted were once hard fought for. That’s why the stories that go a long way back are the ones that keep driving innovation in the future. The digital new world remains a colossus with feet of analog technology. I hope that people will remember this when a robot takes Bill’s place one day...